Training for weightlifting, like any sport, is a long term endeavor. This is why many plans are formulated around an Olympic cycle (four years) and why many high school sports separate freshman athletes from junior and varsity athletes. The goal is to build the athlete up to peak performance at the most important competition of his or her career. This training model is iterative and sequential: the first year of training prepares the athlete for the second year, which prepares them for the third year, which prepares them for the desired results in the fourth year. This is a big picture view of training, not a little picture view of short term and immediate goals. It is very irresponsible to rush the lifter to achieve high results quickly. This will lead to stagnation, burnout, and injury.

The lifter must not try to rush their results and progress by straying too far from a written training plan. The first several years of training must be devoted to technical mastery so much so that technique becomes as natural as breathing. A positive training effect is achieved with <80% of a lifter’s 1RM at this training age. Most of training should revolve around these weights. That does not mean they will not lift over 90% and 100% weights but they will not be lifting them very frequently. In fact, constant maximal effort training can be actively counterproductive if it serves to also hamper the training quality of subsequent practices. It is unnecessary at this training age to be pushing to maximal weights and failure often. It is about building up the body and mind every week, month, and year to do more over time to prepare the lifter for the future plan in 2-3 years time. Even then elite lifters with decades of experience have an average training intensity of ~75% ±2% (1).

This discipline also extends to the coaching of athletes. The coach must not get caught up in a talented lifter’s progress early on. Despite great talent everyone must go through the same progressive training to achieve high results. Results that are rushed tend to not stick (usually resulting in much inconsistency with ≥80% of 1RM) or worse yet, the joints and ligaments are not prepared for such training load and an overuse injury will occur. The former is something that I have seen in myself and in many lifters over the last decade. Those whose training results greatly outstrip their competition results likely will benefit from taking a step back to building up work and tissue capacity.

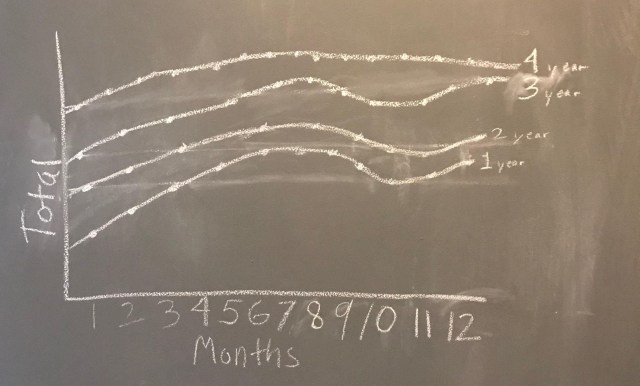

It is necessary to think long term and not to compare results week to week or even month to month. Thinking of training in 8-16 week blocks is too shortsighted and will only yield limited results. I will go as far to say that comparing results within a calendar year is unnecessary. Compare one year of training to the previous year of training. Relatively speaking year to year there should be improvements (weight or sets, volume, intensity and so on). Important competition dates are set consistently in specific quarters of the year. It is better to examine parallel results year to year.

For example, look at competition results from November 2018 and compare those with November of 2017 and 2016 as opposed to those falling within the same calendar year. It is impossible to maintain a high level of fitness year-round and it will fluctuate with the goals of the training phase, creating an apples-to-oranges comparison that ultimately means very little. In some phases, you will be more adapted to training with volume and repetitions rather than single efforts. However if you compare your results year-to-year, they should closely parallel one another with each subsequent year being incrementally higher than the previous.

An elite level example who comes to mind is Rebeka Koha. From observation of her first major competition results in 2011 until now you can see very consistent progress in her total (2). Watching her training videos and interviews you can see that her coach has plans and goals for each training session and competition. She hardly fails in training (if ever) or in competition, there is a constant emphasis on technique even leading into competition, and an increase in the number of training/warmup lifts year to year. Most recently she achieved her highest total at the 2018 World Championships, taking the bronze medal in the total.

It is obvious Koha is one of the most talented lifters right now, making most maximum attempts look easy. She has been making steady, calculated progress every single year with (to my knowledge) no major injuries. A testament to great coaching. An inexperienced coach may have pushed Koha to higher results sooner than later, maybe eking out a few more kilos on her lifts but also likely injuring her in the process or developing her to the point where she is not as consistent.

To quantify Koha’s success even further: she has 21 failed lifts out of 197 taken attempts in 34 international competitions over the course of seven years (2). Her margin for error in competition is around 10%. If we had results for more competitions in Latvia I assume this number would be even lower. Koha even states in interviews she cannot recall missing attempts in training. Imagine the confidence she has walking on stage for any competition.

References:

- “Measurement Techniques.” Science and Practice of Strength Training, by Vladimir M. Zatsiorsky and William J. Kraemer, Human Kinetics, 2006, pp. 70.

- Rebeka Koha. IWRP – Weightlifting Database Available at: http://www.iwrp.net/component/cwyniki/?view=contestant&id_zawodnik=20258. (Accessed: 2nd January 2018)